Peritonitis

Peritonitis is inflammation of the peritoneum, typically caused by bacterial infection due to perforation of an abdominal viscus or contamination of the peritoneal cavity, presenting with severe abdominal pain, rigidity, and systemic sepsis.

Definition

Peritonitis refers to inflammation of the peritoneum — the serous membrane lining the abdominal cavity and covering the abdominal viscera [1][2][3]. The word itself breaks down from Greek: "peri" = around, "tonaion" = stretched (referring to the membrane), "-itis" = inflammation. So literally: inflammation of the membrane stretched around the abdominal contents.

It is one of the commonest surgical emergencies [1][2] and can rapidly become life-threatening. When the peritoneum is inflamed, it becomes oedematous, hyperaemic, and covered with fibrinous exudates [1][2]. This triggers a cascade of sequestration of large amounts of protein-rich fluid into the peritoneal cavity (third-spacing), leading to septicaemia, endotoxaemia, hypovolaemia and shock [1][2]. Left unchecked, this progresses to multi-organ failure and death.

Why is peritonitis so dangerous?

The peritoneum has an enormous surface area (~1.7 m², roughly equal to skin surface area). When inflamed, massive fluid shifts occur across this membrane into the peritoneal cavity ("third-space losses"). Simultaneously, bacteria and endotoxins are absorbed through the highly vascular peritoneal surface into the systemic circulation. This combination of hypovolaemia + sepsis is what kills patients.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Epidemiology

- Peritonitis is a leading cause of emergency surgical admissions worldwide.

- Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) affects approximately 10–30% of hospitalized patients with cirrhotic ascites — highly relevant in Hong Kong given the prevalence of hepatitis B-related cirrhosis.

- CAPD-associated peritonitis is the leading cause of technique failure in peritoneal dialysis patients. Hong Kong has one of the highest rates of peritoneal dialysis utilization globally (>70% of dialysis patients are on PD), making this a particularly high-yield topic locally.

- Secondary peritonitis from perforated peptic ulcer (PPU), perforated appendicitis, and perforated diverticular disease constitutes the bulk of emergency surgical peritonitis cases.

- In the elderly, peritonitis is particularly dangerous because they are poor historians, may be confused or have dementia, history may be inaccurate (rely on care-provider), and peritoneal signs may be mild [1]. This demands a high index of suspicion in any elderly patient with abdominal pain, abdominal distension, fever, leucocytosis, acidosis, or sepsis of unexplained cause [1].

Risk Factors

The following are established risk factors for developing peritonitis [1][2]:

| Risk Factor | Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Ascites | Stagnant ascitic fluid provides an excellent culture medium; impaired peritoneal immune defences |

| Chronic liver disease / cirrhosis | Portal hypertension → ascites; impaired reticuloendothelial system (Kupffer cell dysfunction); decreased complement in ascitic fluid; bacterial translocation from gut |

| Malnutrition | Impaired immune function (reduced immunoglobulin, complement, and cell-mediated immunity) |

| Intra-abdominal malignancy | Tumour necrosis creates a nidus for infection; obstruction may lead to perforation; immunosuppression from cancer itself or chemotherapy |

| Chronic renal disease | Uraemic immunosuppression; PD catheter as a portal of entry |

| Immunosuppression | Steroids, chemotherapy, HIV — all reduce the ability to contain peritoneal infection |

| Splenectomy | Loss of splenic filtration function → susceptibility to encapsulated organisms (e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae) |

Hong Kong Context

In HK, the particularly relevant causes of peritonitis include: (1) SBP in hepatitis B cirrhosis patients, (2) CAPD peritonitis given the high PD utilization, (3) perforated peptic ulcer (H. pylori + NSAID use in the aging population), and (4) perforated appendicitis / diverticulitis. TB peritonitis also remains relevant given Hong Kong's intermediate TB burden.

Anatomy and Function of the Peritoneum

Understanding peritoneal anatomy is essential to understanding patterns of fluid collection, infection spread, and surgical approach.

Structure

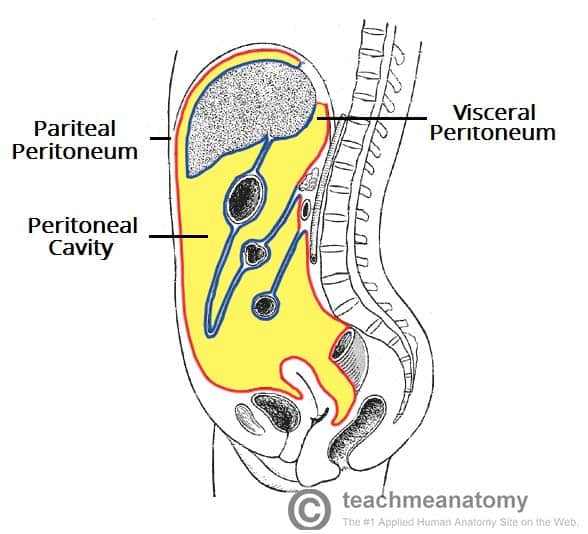

The peritoneum is a continuous serous membrane consisting of:

- Parietal peritoneum: Lines the inner surface of the abdominal and pelvic walls. Innervated by somatic nerves (intercostal nerves T7–T12, subcostal, iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal) → produces sharp, well-localised pain when inflamed.

- Visceral peritoneum: Covers the abdominal viscera. Innervated by autonomic (visceral) nerves → produces dull, poorly-localised, midline pain when inflamed.

This dual innervation explains a classic clinical pattern: early visceral peritoneal irritation (e.g., early appendicitis) causes vague periumbilical pain, but once the parietal peritoneum is involved, pain becomes sharp and localised to the right iliac fossa.

Key Peritoneal Spaces

Knowing peritoneal spaces helps you predict where fluid/pus collects:

- Morison's pouch (hepatorenal recess): The most dependent part of the peritoneal cavity in a supine patient. This is where you look for free fluid on FAST ultrasound [3].

- Right and left subphrenic spaces: Subdiaphragmatic abscesses collect here (e.g., post-splenectomy, perforated peptic ulcer).

- Right and left paracolic gutters: The right paracolic gutter communicates directly with the pelvis and the right subphrenic space — this is why a perforated appendix can cause a right subphrenic abscess (pus tracks up the right paracolic gutter).

- Left infra-mesocolic and right infra-mesocolic spaces: Divided by the root of the small bowel mesentery.

- Pelvis (pouch of Douglas / rectovesical pouch): The most dependent part when the patient is upright. Digital rectal examination can detect pelvic peritonitis as tenderness or a boggy mass here.

Retroperitoneal Organs (NOT covered by peritoneum — important for differential)

These structures, when inflamed, do not cause classical peritoneal signs initially [3]:

- Kidneys, adrenals, ureters

- Aorta / IVC

- Duodenum (D2, D3), ascending and descending colon

- Pancreas (except the tail)

Clinical Pearl

A ruptured AAA or acute pancreatitis can mimic peritonitis but may lack classical peritoneal signs initially because these are retroperitoneal structures. However, if pancreatic enzymes or blood leaks into the peritoneal cavity, secondary peritoneal irritation occurs.

Function of the Peritoneum

- Friction reduction: Mesothelial cells secrete a thin layer of serous fluid (~50–100 mL) that lubricates visceral surfaces.

- Immune defence: Contains macrophages, lymphocytes, and mast cells; the omentum ("policeman of the abdomen") migrates to sites of inflammation to wall off infection.

- Fluid and solute exchange: The large surface area (~1.7 m²) allows significant absorption — this is why peritoneal dialysis works, but also why toxins/bacteria are rapidly absorbed systemically.

- Support and compartmentalization: Mesenteries and ligaments suspend organs and create compartments that can temporarily localise infection.

Etiology

Classification-Based Approach to Etiology

Peritonitis is classified in different ways [1][2]:

- Localized vs. generalized (diffuse) — based on extent

- Bacterial vs. chemical — based on etiology

- Primary vs. secondary vs. tertiary — based on source

This last classification is the most clinically useful and exam-relevant:

1. Primary Peritonitis

Definition: Ascitic fluid infection without a surgically treatable intra-abdominal source of infection [1][2][3]

The infection reaches the peritoneum via haematogenous spread, lymphatic spread, or transmural migration (bacterial translocation) from the gut — there is NO perforation or breach in the GI tract.

a) Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis (SBP)

- Who gets it: Patients with cirrhosis and ascites (especially decompensated liver disease) [2][3]

- Pathophysiology:

- Portal hypertension → intestinal mucosal oedema → impaired mucosal barrier → bacterial translocation (bacteria cross from gut lumen into mesenteric lymph nodes and portal blood)

- Cirrhosis → decreased hepatic reticuloendothelial function (Kupffer cells cannot clear bacteria) → bacteraemia

- Low complement and low opsonic activity in ascitic fluid (ascitic fluid protein < 1 g/dL has poor opsonic capacity) → bacteria proliferate unchecked in ascites

- Organisms: Strep. pneumoniae, Group A Streptococcus, Enteric organisms (especially E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae) [1][2]

- Typically Gram-negative enteric organisms predominate, followed by Gram-positive cocci

b) Tuberculous Peritonitis

- Considered rare in developed countries but relevant in Hong Kong (intermediate TB burden) [1]

- Presentation may be non-specific: low-grade fever, weight loss [1]

- Insidious onset of abdominal pain; peritoneal signs not florid [1]

- Peritoneal fluid: AFB smear often negative; culture takes 4–6 weeks (could be falsely negative) [1]

- Diagnosis is often made by laparoscopy and biopsy of peritoneum — showing caseating granulomata [1]

- Pathophysiology: Haematogenous spread from pulmonary or extrapulmonary TB; can also result from direct spread from infected mesenteric lymph nodes or fallopian tubes

- The ascitic fluid typically has high protein ( > 2.5 g/dL), high lymphocyte count (lymphocyte-predominant), and elevated adenosine deaminase (ADA > 39 U/L)

c) CAPD-Associated Peritonitis

- Primary peritonitis presenting with fever, abdominal pain and turbid PD fluid [2]

- Organisms [1][2]:

- Gram +ve: Staphylococcus sp. (particularly coagulase-negative Staphylococci — from skin flora around catheter exit site), S. aureus

- Gram -ve: E. coli, Campylobacter, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Fungal species

- Risk factors for CAPD peritonitis [2]:

- Catheter-associated infection (exit-site and tunnel infections)

- Lack of sanitary conditions / unhygienic home environment

- Poor dexterity (e.g., diabetic retinopathy → poor hand-eye coordination during exchanges)

- Underlying GI pathology

- Recent invasive procedures (colonoscopy, cystoscopy)

- Nasal carriage of S. aureus

- Constipation (increased bacterial translocation)

- Smoking

Exam Pearl

SBP is MONOmicrobial. If you culture MULTIPLE organisms from the ascitic fluid of a cirrhotic patient, think secondary peritonitis (bowel perforation) rather than SBP — this changes management completely (surgery vs. antibiotics alone).

2. Secondary Peritonitis

Definition: Ascitic fluid infection with a surgically treatable intra-abdominal source of infection [1][2][3]

This accounts for most peritonitis cases [1]. The peritoneal cavity is contaminated by GI contents, bile, urine, or pancreatic juice through a breach in a hollow viscus or direct spread from an infected organ.

Could be localised (e.g., intra-abdominal abscess) or diffuse [1]

Could be preceded by chemical peritonitis (e.g., gastric juice, bile, pancreatic juice, urine & blood) — chemical irritation then becomes secondarily infected [1][2]

Causes (by mechanism)

| Mechanism | Examples |

|---|---|

| Severe inflammation of abdominal organ | Diverticulitis, cholecystitis, appendicitis [1] |

| Perforation of GI tract (spontaneous, trauma, iatrogenic) | PPU, perforated appendix, perforated diverticular disease, perforated colon cancer, Boerhaave syndrome, traumatic bowel injury, colonoscopic perforation [1] |

| Anastomotic leakage | Post-operative leak from bowel anastomosis [1] |

| Ischaemia of abdominal organ | Mesenteric ischaemia → bowel gangrene → perforation [1] |

| Incarcerated / strangulated hernia | Bowel within hernia becomes ischaemic → gangrene → perforation |

Microbiology

Polymicrobial (mixed aerobic + anaerobic flora reflecting GI tract contents) [1][2]:

- Gram-negative: E. coli, Enterobacter, Proteus, Pseudomonas [1]

- Gram-positive: Streptococci, Enterococci [1]

- Anaerobes: Bacteroides [1]

The microbiological profile depends on the level of GI tract perforation:

- Stomach/duodenum: Low bacterial load (acid environment); chemical peritonitis predominates initially. Organisms: Streptococci, Lactobacilli, Candida

- Small bowel: Intermediate bacterial load. Organisms: Gram-negatives + some anaerobes

- Perforation of small bowel is specifically highlighted as having the polymicrobial profile listed above [1]

- Colon: Highest bacterial load (10¹¹ organisms/mL). Heavily polymicrobial including abundant anaerobes (Bacteroides fragilis)

Chemical → Bacterial Peritonitis Timeline

When gastric juice (pH ~1-2) leaks into the peritoneum from a PPU, the initial insult is CHEMICAL — causing intense inflammation but initially sterile. Within 6-12 hours, bacteria colonise the peritoneal fluid and it becomes secondary bacterial peritonitis. This is why early surgery for PPU (within 6 hours) has better outcomes.

3. Tertiary Peritonitis

Definition: Persistent peritonitis after adequate initial therapy [3] — i.e., peritonitis that persists or recurs > 48 hours after apparently adequate surgical source control and antibiotic therapy.

- Caused by opportunistic infections with normally non-pathogenic gut flora [2][3]:

- Staphylococcus infection

- Enterococcus infection

- Candida infection

- Other: coagulase-negative Staphylococci, Enterobacter, Pseudomonas

- Associated with prolonged use of antibiotics in persistent intra-abdominal infection [2] → selects for resistant/opportunistic organisms

- Typically occurs in ICU patients, immunocompromised hosts, or those with ongoing source of contamination

- Carries the worst prognosis of all three types (mortality 30–60%)

Pathophysiology

Understanding the pathophysiology of peritonitis is crucial because it explains every clinical feature and guides treatment:

Sequence of Events

Detailed Pathophysiology

-

Initial insult: Bacteria, chemical irritants (gastric acid, bile, pancreatic enzymes), or both contact the peritoneal mesothelium.

-

Inflammatory response: Mesothelial cells release cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α) and chemokines → recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages → peritoneal hyperaemia and oedema.

-

Fibrinous exudate formation: Increased vascular permeability leads to exudation of protein-rich fluid containing fibrinogen. Fibrinogen is converted to fibrin, creating fibrinous adhesions. These serve a dual purpose:

- Beneficial: Wall off infection (localised peritonitis / abscess formation — the omentum contributes as the "abdominal policeman")

- Detrimental: Can cause bowel obstruction (adhesions), trap bacteria in pockets inaccessible to antibiotics

-

Third-space fluid losses: The inflamed peritoneal surface (1.7 m²) leaks massive amounts of protein-rich fluid into the peritoneal cavity → intravascular volume depletion → hypovolaemia → tachycardia → hypotension → shock.

-

Paralytic ileus: Peritoneal inflammation → reflex inhibition of intestinal motility via:

- Sympathetic overactivation (splanchnic nerves)

- Local inflammatory mediators (prostaglandins, nitric oxide)

- Direct irritation of bowel serosa → Bowel distension → further fluid sequestration within the bowel lumen (yet more third-spacing)

-

Systemic absorption: The peritoneum's vast surface area rapidly absorbs bacteria and endotoxins → bacteraemia / endotoxaemia → systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) → sepsis → septic shock → multi-organ dysfunction.

-

Metabolic consequences:

- Massive protein loss (albumin leaks into peritoneal cavity) → hypoalbuminaemia

- Metabolic acidosis (tissue hypoperfusion + lactate production)

- Respiratory compromise (diaphragmatic splinting from pain + abdominal distension pushing diaphragm up → basal atelectasis)

Classification

Summary Table of Classification Systems

| Classification Axis | Types | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| By source | Primary / Secondary / Tertiary | Whether there is a surgically treatable source [1][2][3] |

| By extent | Localised vs. Generalized (Diffuse) | Localised = contained (e.g., abscess); Generalized = widespread peritoneal contamination [1][2] |

| By etiology | Bacterial vs. Chemical | Chemical (e.g., gastric acid, bile, pancreatic juice) often precedes bacterial infection [1][2] |

Hinchey Classification (for Diverticulitis-Related Peritonitis)

This is specifically geared towards choosing the surgical approach for complicated diverticulitis [4]:

| Stage | Description | Relevance to Peritonitis |

|---|---|---|

| I | Pericolic / mesenteric abscess | Localised, contained |

| II | Walled-off pelvic abscess | Localised, but larger |

| III | Generalised purulent peritonitis | Free pus in peritoneal cavity |

| IV | Generalised faecal peritonitis | Free faecal contamination — worst prognosis |

Clinical Features

The clinical features of peritonitis are a direct reflection of the underlying pathophysiology. I'll separate them into symptoms (what the patient tells you) and signs (what you find on examination), with the pathophysiological basis explained inline.

Symptoms

| Symptom | Pathophysiological Basis |

|---|---|

| Abdominal pain — the hallmark of peritonitis [2] | Inflammation of the parietal peritoneum (somatic innervation → sharp, well-localised pain). Diffuse, continuous, and burning in nature [2]. Initially localised (to the primary pathology, e.g., RIF in appendicitis) and later spreading as peritonitis generalises [1]. Exacerbated by movement and coughing because any movement stretches or jarrs the inflamed parietal peritoneum [1][2]. Patients characteristically lie still (unlike colicky pain where patients writhe around). |

| Fever | Fever is the most common clinical manifestation [2]. Cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α) released from the inflamed peritoneum act on the hypothalamic thermoregulatory centre → ↑ temperature set-point. |

| Hypothermia (in advanced disease) | Mildly hypothermic in patients with advanced disease [2]. Indicates decompensated sepsis — the body can no longer mount a febrile response (immune exhaustion, cardiovascular collapse). This is an ominous sign. |

| Altered mental status | Development of delirium, confusion and cognitive slowing [2]. Caused by infection (septic encephalopathy — cytokines cross the blood-brain barrier, alter neurotransmission) and hepatic decompensation (in cirrhotic patients — ammonia accumulation) [2]. |

| Nausea and vomiting | Peritoneal irritation → vagal afferent stimulation → vomiting centre in medulla. Also due to paralytic ileus (retrograde accumulation of GI contents). |

| Anorexia | Systemic inflammatory cytokines suppress appetite centres in the hypothalamus. |

| Diarrhoea | Alteration in gut flora with overgrowth of one organism, usually E. coli [2]. Also, pelvic peritonitis can irritate the rectum directly, causing tenesmus and frequent small-volume stools. |

| Inability to pass flatus | Paralytic ileus → functional obstruction → no passage of gas. |

| Abdominal distension | Patient notices their abdomen becoming progressively swollen — due to ileus (gas and fluid accumulation in bowel) and peritoneal fluid accumulation. |

Signs

General / Systemic Signs

| Sign | Pathophysiological Basis |

|---|---|

| Fever / Hypothermia | As above — cytokine-mediated vs. septic decompensation [1] |

| Tachycardia | Compensatory response to hypovolaemia (third-space losses) and pain. Also a feature of SIRS/sepsis (catecholamine surge). [1] |

| Tachypnoea | (1) Metabolic acidosis → respiratory compensation (Kussmaul breathing); (2) Abdominal distension pushing diaphragm up → reduced tidal volume → compensatory ↑ RR; (3) Pain-related splinting of respiration; (4) SIRS criterion. [1] |

| Hypotension | Hypovolaemia from third-space fluid losses + sepsis-induced vasodilation (nitric oxide-mediated) + myocardial depression from septic cardiomyopathy. [2] |

| Septic shock | The end-stage haemodynamic consequence: distributive shock (vasodilation) superimposed on hypovolaemic shock. [1] |

| Altered mental status / confusion | Reduced cerebral perfusion (shock) + septic encephalopathy + hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotics. [1][2] |

| Dehydration signs | Dry mucous membranes, sunken eyes, reduced skin turgor, oliguria — all reflecting third-space losses. |

Abdominal Signs

| Sign | Pathophysiological Basis |

|---|---|

| Tenderness | Inflammation of parietal peritoneum → somatic nerve stimulation → pain on palpation. Initially localised to the site of primary pathology; becomes diffuse as peritonitis generalises. [1] |

| Rebound tenderness (Blumberg's sign) | When you release pressure after deep palpation, the inflamed peritoneum springs back and is stimulated → sharp pain. This is a peritoneal sign indicating parietal peritoneal irritation. [1] |

| Guarding | Involuntary contraction of the abdominal wall muscles overlying the inflamed peritoneum — a protective reflex mediated by the spinal reflex arc (peritoneal irritation → afferent signal via intercostal nerves → spinal cord → efferent motor response → muscle contraction). [1] |

| Board-like rigidity | The extreme form of guarding seen in diffuse peritonitis — the entire abdominal wall is rigid and "hard as a board" due to generalised involuntary muscle spasm. Classic for a perforated viscus with generalised peritonitis. [2] |

| Abdominal distension | Paralytic ileus → gas and fluid accumulate in dilated bowel loops. Also, free fluid/pus in the peritoneal cavity. [2] |

| Shifting dullness | Large volume of free peritoneal fluid (ascites/pus/blood) shifts with gravity when the patient changes position → dullness shifts. [2] |

| Absence of bowel sounds (paralytic ileus) | Peritoneal inflammation causes reflex inhibition of bowel motility — sympathetic overactivation inhibits peristalsis; local inflammatory mediators (prostaglandins, NO) paralyse smooth muscle. A "silent abdomen" on auscultation is ominous. [1][2] |

| Percussion tenderness | Tapping the abdomen jars the inflamed peritoneum → pain. A gentler way to elicit peritoneal irritation than deep palpation. |

| Digital rectal examination — tenderness | Pelvic peritonitis causes tenderness on palpation of the pouch of Douglas / rectovesical pouch via DRE. May feel a boggy, tender mass if a pelvic abscess is present. |

The Classic Peritoneal Triad: T + G + R

Special Considerations

Peritonitis in the elderly deserves special mention [1]:

- Poor historian — may be confused or have dementia

- History may be inaccurate → rely on care-provider

- Peritoneal signs may be mild — elderly patients have thinner abdominal musculature (less guarding), reduced inflammatory response, and may be on analgesics/steroids that mask signs

- Need a high index of suspicion: any elderly patient with abdominal pain, abdominal distension, fever, leucocytosis, acidosis, or sepsis of unexplained cause should be investigated for peritonitis [1]

Exam Trap: Absence of Peritoneal Signs ≠ Absence of Peritonitis

Several groups may NOT show classical peritoneal signs despite having peritonitis: (1) Elderly/demented patients, (2) Immunosuppressed patients (steroids suppress inflammation), (3) Patients with ascites (fluid cushion prevents direct peritoneal contact), (4) Patients on strong analgesics. Always correlate with blood tests (leucocytosis, raised CRP/lactate) and imaging.

Symptoms and Signs of the Primary Pathology

Peritonitis clinical features include symptoms and signs of the primary pathology [1]. This means you will also see features specific to whatever caused the peritonitis:

- PPU: Sudden-onset epigastric pain, preceding dyspepsia, NSAID/steroid use

- Appendicitis: Migratory RIF pain, anorexia, Rovsing's/psoas/obturator signs

- Diverticulitis: LIF pain (or RIF in Asian right-sided diverticular disease), altered bowel habit

- Cholecystitis: RUQ pain, Murphy's sign, jaundice

- Pancreatitis: Epigastric pain radiating to back, raised amylase/lipase

- SBP: History of liver disease, jaundice, ascites, encephalopathy

- CAPD peritonitis: Turbid PD fluid, catheter exit-site erythema/discharge

Peritoneal Fluid Analysis

Peritoneal fluid analysis is critical for distinguishing the type and cause of peritonitis [1][2]:

| Parameter | What It Tells You |

|---|---|

| Character: serous, blood-stained, purulent, bile-stained, faeculent | Serous = SBP or early; Blood-stained = trauma/malignancy/pancreatitis; Purulent = established bacterial peritonitis; Bile-stained = perforated GB or biliary injury; Faeculent = perforated bowel [1] |

| Cell counts: Neutrophil count > 500/μL | Indicative of bacterial peritonitis. SBP diagnosed at PMN ≥ 250 cells/mm³ [1][2] |

| Low glucose, high protein, high LDH compared to serum | Suggests secondary peritonitis (bacteria consume glucose; damaged cells release LDH and protein). Runyon's criteria. [1] |

| Gram stain | Rapid identification of organism morphology. Positive in ~25% of SBP (low sensitivity). |

| Cultures: aerobic, anaerobic, AFB, fungal | Definitive identification. Inoculate ascitic fluid into blood culture bottles at bedside to improve yield. [1] |

| Amylase | ↑ Amylase in peritoneal fluid → perforated gut (duodenal/small bowel) or pancreatitis [1][3] |

| Creatinine | ↑ Creatinine in peritoneal fluid (higher than serum) → urinary tract injury / bladder perforation [1] |

↑ Amylase / bile-stained / faeculent peritoneal fluid indicates perforated GI tract [3]

Summary: Connecting Pathophysiology to Clinical Features

High Yield Summary

Definition: Peritonitis = inflammation of the peritoneum; a surgical emergency.

Classification:

- Primary: No surgical source (SBP, CAPD, TB peritonitis) — monomicrobial

- Secondary: Surgical source present (perforation, ischaemia, inflammation) — polymicrobial — accounts for most cases

- Tertiary: Persistent despite adequate therapy — opportunistic organisms (Candida, Enterococcus, Staph)

Also classified by: Localised vs. diffuse; Bacterial vs. chemical

Risk factors: Ascites, CLD, malnutrition, malignancy, CKD, immunosuppression, splenectomy

Pathophysiology cascade: Peritoneal insult → hyperaemia + oedema + fibrinous exudates → third-space loss (hypovolaemia) + bacterial absorption (septicaemia) → shock + MOF

Key clinical features:

- Symptoms: Burning abdominal pain (worse with movement/cough), fever (hypothermia in advanced disease), altered mental status, nausea/vomiting, diarrhoea

- Signs: Tenderness + Guarding + Rebound (T+G+R) = peritoneal signs; board-like rigidity; absent bowel sounds; tachycardia, hypotension, tachypnoea

- Elderly: Mild peritoneal signs — high index of suspicion needed

Peritoneal fluid analysis: Character, cell count (PMN > 500), glucose/protein/LDH, Gram stain, cultures (aerobic/anaerobic/AFB/fungal), amylase, creatinine

If free gas on erect CXR + florid peritoneal signs → exploratory laparotomy

Active Recall - Peritonitis (Definition, Epidemiology, Anatomy, Etiology, Pathophysiology, Classification, Clinical Features)

1. What are the three classifications of peritonitis by source, and what distinguishes each?

Show mark scheme

Primary = no surgically treatable intra-abdominal source (e.g. SBP, CAPD, TB); Secondary = surgically treatable source present (e.g. perforation, ischaemia, inflammation) - accounts for most cases; Tertiary = persistent peritonitis after adequate initial therapy - opportunistic organisms (Candida, Enterococcus, Staph).

2. Why does peritonitis cause hypovolaemia and shock? Explain the pathophysiological cascade.

Show mark scheme

Inflamed peritoneum (surface area ~1.7 m2) becomes hyperaemic, oedematous, covered with fibrinous exudates. Massive protein-rich fluid sequestered into peritoneal cavity (third-spacing). Intravascular volume depleted. Also paralytic ileus causes further fluid sequestration in dilated bowel. Combined with sepsis-induced vasodilation leads to hypovolaemic + distributive shock.

3. What is the classic peritoneal triad on examination, and what is the pathophysiological basis of guarding?

Show mark scheme

Tenderness + Guarding + Rebound (T+G+R). Guarding = involuntary contraction of abdominal wall muscles via spinal reflex arc: inflamed parietal peritoneum stimulates somatic afferents (intercostal nerves) to spinal cord, which sends efferent motor signals causing overlying muscle contraction as a protective reflex.

4. SBP is monomicrobial while secondary peritonitis is polymicrobial. Name the common organisms for each and explain why this distinction matters clinically.

Show mark scheme

SBP: monomicrobial - E. coli, Klebsiella, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Group A Strep. Secondary: polymicrobial - Gram-neg (E. coli, Enterobacter, Proteus, Pseudomonas), Gram-pos (Streptococci, Enterococci), Anaerobes (Bacteroides). If multiple organisms cultured from ascitic fluid in a cirrhotic patient, suspect secondary peritonitis (bowel perforation) rather than SBP - changes management from antibiotics alone to surgery.

5. Why are elderly patients with peritonitis particularly dangerous? List the clinical pitfalls.

Show mark scheme

Poor historians, may be confused or demented. History may be inaccurate, need to rely on care-providers. Peritoneal signs may be mild (thinner abdominal muscles, reduced inflammatory response, may be on steroids/analgesics). Need high index of suspicion: look for abdominal pain, distension, fever, leucocytosis, acidosis, unexplained sepsis. Delayed diagnosis leads to higher morbidity and mortality.

6. In peritoneal fluid analysis, what does bile-stained fluid, raised amylase, and raised creatinine each indicate?

Show mark scheme

Bile-stained = biliary perforation or gallbladder injury. Raised amylase = perforated duodenum/small bowel or pancreatitis. Raised creatinine (higher than serum) = bladder perforation or urinary tract injury.

References

[1] Lecture slides: GC 195. Lower and diffuse abdominal pain RLQ problems; pelvic inflammatory disease; peritonitis and abdominal emergencies.pdf (p34–43) [2] Senior notes: felixlai.md (Peritonitis section, p738–743; CAPD peritonitis section, p866) [3] Senior notes: maxim.md (Section 2.5 Peritonitis) [4] Senior notes: felixlai.md (Hinchey classification, diverticular disease section, p637)

Differential Diagnosis of Peritonitis

Why Is the Differential Diagnosis of Peritonitis Important?

Peritonitis is not a single disease — it is a clinical syndrome (inflammation of the peritoneum) that can be caused by dozens of different conditions. When a patient presents with peritoneal signs (tenderness, guarding, rebound) [1], your job is twofold:

- Confirm peritonitis — could the peritoneal signs be mimicked by something else (e.g., abdominal wall pathology, retroperitoneal disease, medical causes)?

- Identify the underlying cause — because management differs dramatically (e.g., SBP = antibiotics alone vs. perforated viscus = emergency surgery).

The DDx is best approached systematically by thinking about what can irritate the peritoneum from first principles: (a) things that perforate/leak into the peritoneal cavity, (b) organs that inflame and involve the adjacent peritoneum, (c) primary peritoneal disease, and (d) "mimics" — conditions that look like peritonitis but aren't.

Framework for Differential Diagnosis

I'll organize this in two layers:

Layer 1 — Differentiating BETWEEN the causes of peritonitis (i.e., once you know the peritoneum is inflamed, what's the aetiology?)

Layer 2 — Differentiating peritonitis FROM its mimics (i.e., conditions that present similarly but the peritoneum is not the primary problem)

Layer 1: Causes of Peritonitis — Differential by Type

This is essentially the aetiological differential: "What caused the peritonitis?"

A. Primary Peritonitis

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) | History of liver cirrhosis and ascites [1][2]. Fever, abdominal pain, altered mental status. Ascitic fluid PMN ≥ 250 cells/mm³, monomicrobial culture. No free gas on imaging. Risk factors: ascites, malnutrition, immunosuppression, CLD, CKD, splenectomy, intra-abdominal malignancy [1]. |

| Tuberculous peritonitis | Presentation may be non-specific: low-grade fever, weight loss, insidious onset of abdominal pain [1]. Peritoneal signs not florid [1]. Ascitic fluid is lymphocyte-predominant (not neutrophil-predominant like SBP), high protein ( > 2.5 g/dL), elevated ADA. AFB smear often negative; culture takes 4–6 weeks (could be falsely negative) [1]. Diagnosis often made by laparoscopy and biopsy of peritoneum [1]. HK context: intermediate TB burden, consider in immigrants/immunosuppressed. |

| CAPD-associated peritonitis | Patient on peritoneal dialysis with turbid PD effluent, abdominal pain ± fever [2]. PD fluid WBC ≥ 100/mm³ with > 50% PMN. Look for exit-site infection (erythema, discharge at catheter site). Organisms: coagulase-negative Staph (from skin), S. aureus, Gram-negatives [2]. |

SBP vs. Secondary Peritonitis in a Cirrhotic Patient — Critical Distinction

Both can present identically in a cirrhotic patient with ascites. If you culture multiple organisms from the ascitic fluid, or if Runyon's criteria are met (protein > 1 g/dL, glucose < 50 mg/dL, LDH > ULN for serum [2]), think secondary peritonitis — this patient needs surgery, not just antibiotics. Missing a perforation in a cirrhotic is a classic fatal error.

B. Secondary Peritonitis — The Main Differentials

Accounts for most peritonitis [1]. The differential here is essentially: which organ has perforated, become ischaemic, or is severely inflamed?

By Mechanism: Perforation

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Perforated peptic ulcer (PPU) | Sudden-onset severe epigastric pain → rapidly becomes diffuse. History of dyspepsia, NSAID/steroid use, H. pylori. Board-like rigidity (chemical peritonitis from gastric acid). Free gas under diaphragm on erect CXR is the classic finding. Chemical peritonitis preceded by bacterial peritonitis [1] — gastric acid initially sterile, secondary infection follows in 6–12 hours. |

| Perforated appendicitis | Initial periumbilical pain → migrating to RIF (the classic visceral → somatic shift). Fever, anorexia, nausea. McBurney's point tenderness, Rovsing's sign, psoas sign [5]. If perforation occurs → generalised peritonitis with diffuse tenderness and guarding. Peak age 20s–30s [2]. Grade 5: Perforated with diffuse peritonitis [2]. |

| Perforated diverticulitis | LIF pain (or RIF in Asian population with right-sided diverticular disease [2]). History of altered bowel habit, older age (mean 63 years [2]). CT: bowel wall thickening, pericolonic fat stranding ± free gas/fluid. Hinchey III = generalised purulent peritonitis; Hinchey IV = generalised faecal peritonitis [2][6]. |

| Perforated colorectal cancer | May present acutely with peritonitis. History of weight loss, altered bowel habit, PR bleeding, iron-deficiency anaemia. CT: mass lesion with perforation. Similar features to diverticulitis on imaging — CRC can only be excluded with colonoscopy after resolution of acute inflammation [2]. |

| Perforations of GI tract: spontaneous, trauma, iatrogenic | Post-colonoscopy perforation (iatrogenic), blunt/penetrating abdominal trauma, spontaneous perforation of stercoral ulcer in severe constipation [1]. |

| Boerhaave syndrome | Perforation of oesophagus (usually distal) after forceful vomiting. Severe chest/epigastric pain, subcutaneous emphysema, Hamman's sign (mediastinal crunch). Leads to mediastinitis ± peritonitis if perforation is below diaphragm. |

By Mechanism: Severe Inflammation

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Cholecystitis | RUQ pain, fever, Murphy's sign (+ve). Inflammatory process may remain localised or spread to involve the peritoneum (localised peritonitis → diffuse if perforated). USG: thickened GB wall, pericholecystic fluid, gallstones [1]. |

| Cholangitis | Charcot's triad: fever + jaundice + RUQ pain. Reynold's pentad adds hypotension + confusion (sepsis). Biliary obstruction → ascending infection. |

| Pancreatitis | Epigastric pain radiating to back, relieved by leaning forward. Markedly elevated serum amylase/lipase ( > 3× ULN). Could be preceded by chemical peritonitis [1] — pancreatic enzymes leak into the peritoneal cavity causing chemical irritation. Grey-Turner (flank ecchymosis) and Cullen (periumbilical ecchymosis) signs in severe haemorrhagic pancreatitis [5]. |

| Diverticulitis (uncomplicated) | LIF pain/tenderness, low-grade fever, altered bowel habit. Severe inflammation of abdominal organ causing localised peritoneal irritation without free perforation [1]. |

| Appendicitis (uncomplicated) | RIF pain, low-grade fever, anorexia. Localised peritonitis in RIF before perforation occurs [1]. |

By Mechanism: Ischaemia

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Ischaemic bowel (acute mesenteric ischaemia) | "Pain out of proportion to examination" in the early stages (visceral pain with minimal signs). Later → bowel infarction → full peritonitis with guarding, rigidity. Risk factors: AF (embolic), atherosclerosis, low-flow states. Markedly elevated lactate and metabolic acidosis. Ischaemia of abdominal organ e.g. bowel [1]. |

| Strangulated / incarcerated hernia | Irreducible, tender lump at hernia site (inguinal, femoral, incisional). Bowel within the hernia becomes ischaemic → gangrene → perforation → peritonitis. Features of intestinal obstruction (vomiting, distension, constipation) may coexist. |

By Mechanism: Other

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Anastomotic leakage | Post-operative patient (typically day 3–7 after bowel surgery). Sudden deterioration with fever, tachycardia, abdominal pain, peritoneal signs. Peritoneal fluid may be faeculent or bile-stained [1][3]. |

Layer 2: Conditions That Mimic Peritonitis ("Pseudo-peritonitis")

These are critical because they can present with abdominal pain and even some degree of abdominal tenderness/guarding, but the peritoneum itself is NOT the primary site of pathology. Operating on these patients is either unnecessary or harmful.

Retroperitoneal Conditions

Retroperitoneal organs are NOT covered by peritoneum [3], so inflammation of these structures does not directly cause classical peritoneal signs — but the pain may be severe and can be confusing:

| Condition | How to Differentiate |

|---|---|

| Ruptured AAA | Sudden severe abdominal/back pain, hypotension, pulsatile abdominal mass. May mimic peritonitis with abdominal tenderness. CT angiography diagnostic. Ecchymosis signs (Grey-Turner, Cullen) overlap with severe pancreatitis [5]. |

| Acute pancreatitis | Retroperitoneal organ → signs may be less classical initially. Raised amylase/lipase ( > 3× ULN). Pain radiating to back. No free gas on CXR (distinguishes from PPU). |

| Perinephric abscess / pyelonephritis | Flank pain, fever, costovertebral angle tenderness. Pyuria and bacteriuria on urinalysis. CT: perinephric collection. |

| Ureteric colic | Severe colicky loin-to-groin pain. Restless patient (writhing, cannot stay still — opposite to peritonitis where patients lie still). Haematuria on dipstick. CT KUB diagnostic. |

Gynaecological Conditions (Critical DDx in Women of Reproductive Age)

These are extremely important — several of these present almost identically to appendicitis or pelvic peritonitis:

| Condition | How to Differentiate |

|---|---|

| Ruptured ectopic pregnancy | Life-threatening. Amenorrhoea + positive β-hCG + acute lower abdominal pain + haemodynamic instability. Free fluid on FAST USG. Always do a pregnancy test in any woman of reproductive age with acute abdominal pain [2]. |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) | Bilateral lower abdominal pain, fever, purulent vaginal discharge. Pain worsens during/shortly after menses or with coitus. Cervical motion tenderness ("chandelier sign") on bimanual examination [2]. |

| Tubo-ovarian abscess | Complication of PID. Inflammatory mass in adnexa. High fever, toxic. Can rupture → generalised peritonitis [2]. |

| Ruptured ovarian cyst | Sudden onset of unilateral lower abdominal pain, often during exercise or intercourse. May cause haemoperitoneum. Diagnosis: USG showing free fluid + collapsed cyst [2]. |

| Ovarian / fallopian tube torsion | Sudden severe unilateral pelvic pain, nausea/vomiting. Whirlpool sign on Doppler USG. Adnexal mass with absent blood flow [2]. |

| Endometriosis / Endometrioma | Cyclical pelvic pain, dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia. Endometrioma rupture can cause chemical peritonitis (chocolate-coloured fluid). |

Golden Rule

Always do a pregnancy test (urine or serum β-hCG) in ANY woman of reproductive age presenting with acute abdominal pain. A ruptured ectopic pregnancy can kill within hours. This is the single most important "don't miss" diagnosis.

Medical Causes ("Non-Surgical Abdomen" Mimicking Peritonitis)

These are conditions where laparotomy is not indicated — operating on these patients causes harm:

| Condition | Why It Mimics Peritonitis | How to Differentiate |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) | Severe abdominal pain (mechanism: gastric dilatation, mesenteric ischaemia from dehydration, metabolic irritation of peritoneum). Can cause guarding and even board-like rigidity. | Hyperglycaemia, ketonaemia, metabolic acidosis with high anion gap. History of type 1 DM or missed insulin. Kussmaul breathing, fruity breath. ABG diagnostic [4]. |

| Acute MI (especially inferior) | Inferior MI can refer pain to the epigastrium via diaphragmatic irritation (shared innervation T7–T9). | ECG, troponin. Risk factors for IHD. No peritoneal signs on careful examination. |

| Addisonian crisis | Severe abdominal pain, hypotension, vomiting. | Hyperkalaemia, hyponatraemia, hypoglycaemia. History of steroid use/withdrawal. Low random cortisol. |

| Herpes zoster (shingles) | Dermatome distribution of pain may precede the rash by days → can mimic peritonitis of the corresponding abdominal quadrant. | Unilateral, dermatomal. Vesicular rash eventually appears. |

| Acute porphyria | Severe colicky abdominal pain, neuropsychiatric symptoms, dark urine. | Urine porphobilinogen elevated. Young woman. |

| Hypercalcaemia | Abdominal pain, constipation, confusion ("bones, stones, groans, moans"). | Serum calcium elevated. PTH, malignancy workup. |

| Sickle cell crisis | Vaso-occlusive crisis can cause severe abdominal pain mimicking an acute abdomen. | Known sickle cell disease. Blood film, Hb electrophoresis. |

| Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF) | Recurrent episodes of sterile peritonitis with fever, serositis. | Mediterranean ethnicity. Self-limiting episodes. Responds to colchicine. MEFV gene mutation. |

The 'Medical Abdomen' Trap

DKA is the classic exam trap. A young patient with Type 1 DM presents with severe abdominal pain, vomiting, and abdominal rigidity — the surgical team is called for a "peritonitis." But checking a blood glucose and ABG reveals the diagnosis. Always check glucose and ABG in any patient with unexplained peritonitis. Fever, leucocytosis, acidosis, sepsis of unexplained cause in the elderly [1] could also be a medical abdomen — but equally could be masked surgical pathology, so maintain high suspicion.

Abdominal Wall Pathology

| Condition | How to Differentiate |

|---|---|

| Rectus sheath haematoma | Localized abdominal wall pain and mass. Carnett's sign positive (tenderness increases when patient tenses abdominal wall by lifting head — opposite to intra-abdominal pathology where tenderness decreases with tensing because the tensed muscle "protects" the viscera). History of anticoagulation, trauma, or vigorous coughing. CT diagnostic. |

Extra-abdominal Conditions

| Condition | How to Differentiate |

|---|---|

| Lower lobe pneumonia / basal pleurisy | Diaphragmatic irritation → referred upper abdominal pain. Cough, dyspnoea, pleuritic chest pain. CXR shows consolidation. |

| Testicular torsion | Acute scrotal pain may be referred to the lower abdomen. Always examine the scrotum in a young male with lower abdominal pain. |

Systematic Approach — Decision Diagram

Key Clinical Clues to Narrow the Differential

| Clinical Clue | Points Towards |

|---|---|

| Free gas under diaphragm on erect CXR | Perforated hollow viscus (PPU, perforated bowel) → proceed to laparotomy [3] |

| Bile-stained peritoneal fluid | Biliary perforation / GB injury [1][3] |

| Faeculent peritoneal fluid | Perforated colon [1][3] |

| ↑ Amylase in peritoneal fluid | Pancreatitis or perforated duodenum/small bowel [1][3] |

| ↑ Creatinine in peritoneal fluid | Bladder / urinary tract injury [1] |

| Monomicrobial culture from ascitic fluid | SBP (primary peritonitis) [1][2] |

| Polymicrobial culture from ascitic fluid | Secondary peritonitis (perforation/breach) [1][2] |

| Lymphocyte-predominant ascitic fluid + high ADA | TB peritonitis [1] |

| Turbid PD effluent in a PD patient | CAPD peritonitis [2] |

| Positive β-hCG | Ruptured ectopic pregnancy |

| Cervical motion tenderness | PID |

| High anion gap metabolic acidosis + hyperglycaemia | DKA (medical mimic) |

| Pain out of proportion to examination | Mesenteric ischaemia (early) |

| Dermatomal pain pattern | Herpes zoster |

Special Consideration: Differentiating Diverticulitis from CRC

This is specifically highlighted in the senior notes [2] and worth emphasising:

- Similar clinical features and bowel wall thickening on abdominal CT scan [2]

- Features suggestive of acute diverticulitis include: presence of pericolonic and mesenteric inflammation, involvement of > 10 cm of colon, and absence of enlarged pericolonic lymph nodes on CT [2]

- CRC can only be excluded with colonoscopy after resolution of acute inflammation [2] — you should NEVER do a colonoscopy during the acute episode (risk of perforation)

- In Asian populations, right-sided diverticulitis is significantly more common and is OFTEN confused with acute appendicitis [2]

Special Consideration: DDx of RIF Pain (Appendicitis vs. Everything Else)

Since appendicitis progressing to peritonitis is so common, and RIF pain has a broad differential [2]:

GI: Acute appendicitis, right-sided diverticulitis (more common in Asians), Meckel's diverticulitis, acute ileitis (Yersinia, Campylobacter, Salmonella), Crohn's disease, caecal carcinoma, mesenteric adenitis

O&G: Ruptured ectopic pregnancy, PID, tubo-ovarian abscess, ruptured ovarian cyst, ovarian/fallopian tube torsion, endometriosis [2]

Urological: Ureteric colic, UTI/pyelonephritis

Other: Strangulated inguinal/femoral hernia, psoas abscess

High Yield Summary — Differential Diagnosis of Peritonitis

Layer 1 — Causes of peritonitis (what's the aetiology?):

- Primary: SBP (cirrhosis), CAPD peritonitis (PD patient), TB peritonitis (insidious, laparoscopic biopsy)

- Secondary (most common): Perforation (PPU, appendix, diverticular, CRC, trauma), Inflammation (cholecystitis, appendicitis, pancreatitis, diverticulitis), Ischaemia (mesenteric ischaemia, strangulated hernia), Anastomotic leak

- Tertiary: Persistent despite adequate Rx — opportunistic organisms

Layer 2 — Mimics of peritonitis:

- Medical: DKA (classic trap!), inferior MI, Addisonian crisis, porphyria, herpes zoster, hypercalcaemia, sickle cell, FMF

- Retroperitoneal: Ruptured AAA, pancreatitis, perinephric abscess, ureteric colic

- Gynaecological (always pregnancy test!): Ruptured ectopic, PID, TOA, ovarian cyst rupture, torsion

- Abdominal wall: Rectus sheath haematoma (Carnett's sign)

- Extra-abdominal: Basal pneumonia, testicular torsion

Key distinguishing clues: Free gas = perforation → laparotomy. Bile-stained/faeculent fluid = perforated GI tract. Monomicrobial = primary. Polymicrobial = secondary. Lymphocytic + high ADA = TB. Turbid PD effluent = CAPD peritonitis. Positive β-hCG = ectopic. High AG metabolic acidosis = DKA.

Active Recall - Differential Diagnosis of Peritonitis

1. A cirrhotic patient with ascites develops fever and abdominal pain. Ascitic fluid culture grows 3 different organisms. Is this SBP or secondary peritonitis, and why does the distinction matter?

Show mark scheme

This is secondary peritonitis, not SBP. SBP is monomicrobial; polymicrobial culture suggests a breach in the GI tract (e.g. perforation). The distinction matters because SBP is treated with antibiotics alone (3rd-gen cephalosporin), whereas secondary peritonitis requires surgical intervention. Runyon's criteria can further support secondary peritonitis: protein > 1 g/dL, glucose < 50 mg/dL, LDH > ULN for serum.

2. Name 3 medical (non-surgical) conditions that can mimic peritonitis and explain why DKA is the classic trap.

Show mark scheme

DKA, acute inferior MI, Addisonian crisis (also: porphyria, herpes zoster, hypercalcaemia, sickle cell crisis, FMF). DKA mimics peritonitis because severe metabolic derangement causes gastric dilatation, mesenteric ischaemia from dehydration, and metabolic irritation of the peritoneum, producing genuine abdominal tenderness and even board-like rigidity. Performing a laparotomy on a DKA patient is harmful; checking glucose and ABG reveals the diagnosis.

3. A 28-year-old woman presents with acute RIF pain, fever, and localised peritonitis. List 4 important differential diagnoses and state the single most important bedside test you must not forget.

Show mark scheme

DDx: Acute appendicitis, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, PID/tubo-ovarian abscess, ruptured ovarian cyst, right-sided diverticulitis (more common in Asians), ovarian torsion, ureteric colic. The single most important test is a urine pregnancy test (beta-hCG) to exclude ruptured ectopic pregnancy, which is life-threatening.

4. How do you differentiate TB peritonitis from SBP based on clinical presentation and peritoneal fluid analysis?

Show mark scheme

TB peritonitis: insidious onset, low-grade fever, weight loss, peritoneal signs not florid. Ascitic fluid is LYMPHOCYTE-predominant (vs. neutrophil-predominant in SBP), high protein > 2.5 g/dL, elevated ADA > 39 U/L. AFB smear often negative, culture takes 4-6 weeks and may be falsely negative. Diagnosis often requires laparoscopy and peritoneal biopsy showing caseating granulomata. SBP: acute onset, neutrophil-predominant ascites (PMN >= 250), usually in context of decompensated cirrhosis.

5. What peritoneal fluid findings indicate a perforated GI tract rather than primary peritonitis?

Show mark scheme

Bile-stained fluid (biliary perforation), faeculent fluid (colonic perforation), raised amylase (duodenal/small bowel perforation or pancreatitis), raised creatinine above serum level (bladder perforation). Also: polymicrobial culture, and Runyon's criteria positive (protein > 1 g/dL, glucose < 50 mg/dL, LDH > ULN).

References

[1] Lecture slides: GC 195. Lower and diffuse abdominal pain RLQ problems; pelvic inflammatory disease; peritonitis and abdominal emergencies.pdf (p34–43) [2] Senior notes: felixlai.md (Peritonitis section p738–743; Acute appendicitis DDx p728–729; Diverticulitis DDx p641; CAPD peritonitis p866; SBP p449–450) [3] Senior notes: maxim.md (Section 2.5 Peritonitis; Acute abdomen DDx p44–46; Appendicitis p179; Diverticulitis p194) [4] Senior notes: maxim.md (Acute abdomen DDx — medical causes: DKA, hypercalcaemia, herpes zoster, porphyria, p44) [5] Senior notes: felixlai.md (Ruptured AAA DDx p910–911) [6] Senior notes: felixlai.md (Hinchey classification p637)

Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnosis of peritonitis is fundamentally clinical — you see a sick patient with peritoneal signs and you act. However, to classify the type of peritonitis (primary vs. secondary) and guide the correct treatment pathway (antibiotics alone vs. surgery), you need specific diagnostic criteria for each subtype. Let me walk through each one and explain the logic behind every threshold.

1. Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis (SBP)

Diagnosis requires ALL of the following [2]:

| Criterion | Threshold | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Ascitic fluid PMN count | ≥ 250 cells/mm³ | PMNs (neutrophils) are the first-responders to bacterial infection. A count ≥ 250 is the validated cut-off that balances sensitivity and specificity for SBP. Why neutrophils specifically? Because they are recruited to the peritoneal cavity within hours of bacterial invasion, whereas lymphocytes predominate in TB or malignancy. |

| Peritoneal fluid culture | Positive | Confirms infection and identifies the organism. Monomicrobial — typically Gram-negative enterics (E. coli, Klebsiella) or Gram-positive cocci (Streptococcus, Staphylococcus) [1][2]. Culture must be inoculated into blood culture bottles at the bedside (not just sent in a plain pot) to improve yield — SBP has low bacterial density in ascitic fluid. |

| Secondary causes excluded | Must rule out surgically treatable source | If you miss a perforation and treat as SBP with antibiotics alone, the patient will die. Runyon's criteria (see below) help distinguish. |

Important Variants of SBP [2]

| Variant | PMN Count | Culture | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classic SBP | ≥ 250/mm³ | Positive | Treat with antibiotics |

| Culture-negative neutrocytic ascites (CNNA) | ≥ 250/mm³ | Negative | Almost certainly early SBP — treat as SBP anyway. Culture is negative because bacterial density is low. |

| Non-neutrocytic bacterascites (NNBA) | < 250/mm³ | Positive | May resolve spontaneously or progress to SBP. Repeat paracentesis in 48h. Treat only if symptomatic. |

Why is PMN ≥ 250 the threshold for SBP, not ≥ 500?

The lecture slides state neutrophil count > 500/μL as a general peritoneal fluid marker for peritonitis [1]. However, for SBP specifically, the threshold is PMN ≥ 250/mm³ [2] — this lower threshold was established because cirrhotic patients are immunosuppressed and mount a weaker inflammatory response. Waiting for PMN > 500 would miss early SBP and delay life-saving antibiotics. The PMN ≥ 250 cut-off has ~93% sensitivity.

2. CAPD-Associated Peritonitis

Diagnosis requires at least 2 of 3 criteria [2]:

| Criterion | Threshold | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | Abdominal pain or cloudy effluent ± fever | The turbidity of PD effluent is due to increased WBCs — this is often the first sign noticed by the patient before pain develops. Absence of fever does not exclude peritonitis since the infection can be localised or low-grade [2]. |

| PD fluid cell count | WBC ≥ 100 cells/mm³ with PMN > 50% after dwell time ≥ 2 hours | Note this is LOWER than SBP threshold (100 vs. 250). The cutoff is lower because dextrose in PD solutions provides an excellent growth medium for bacteria — rapid proliferation means even a "low" count indicates significant infection [2]. The 2-hour dwell-time requirement standardises the count (shorter dwells may dilute cells). |

| PD effluent culture | Positive | Gram stain is positive in only ~40% of cases, so a negative Gram stain does NOT exclude infection. Effluent must be cultured (aerobic, anaerobic, AFB, fungal). |

Clinical Pearl

In CAPD peritonitis, do not wait for laboratory confirmation or culture result — start antibiotics as early as possible if the diagnosis is clinically certain, since delayed treatment carries a worse outcome [2]. This is because dextrose-containing PD fluid accelerates bacterial growth, and the peritoneal membrane becomes progressively damaged with ongoing infection, leading to fibrosis and eventual PD failure.

3. Secondary Bacterial Peritonitis (Distinguishing from SBP in a Cirrhotic Patient)

This uses Runyon's criteria — at least 2 of 3 in the ascitic fluid [2]:

| Criterion | Threshold | Why This Distinguishes Secondary from Primary |

|---|---|---|

| Total protein | > 1 g/dL (10 g/L) | In SBP, ascitic fluid protein is low (poor opsonic activity — this is WHY they get SBP in the first place). In secondary peritonitis, the perforation allows protein-rich intestinal/serum contents to flood the peritoneal cavity → high protein. |

| Glucose | < 50 mg/dL (2.8 mmol/L) | Neutrophils consume large amounts of glucose [2]. Secondary peritonitis has a much higher neutrophil and bacterial burden than SBP → more glucose consumed → lower glucose. In SBP, the ascitic fluid neutrophil count is lower (by comparison) and glucose remains relatively preserved. |

| LDH | > Upper limit of normal for serum | LDH is released from dying cells. In secondary peritonitis, there is massive tissue destruction (from perforation, ischaemia) → ↑↑↑ LDH [2]. In SBP, LDH is only mildly elevated. |

Additional clues for secondary peritonitis (not part of Runyon's criteria but highly useful):

- Polymicrobial culture (vs. monomicrobial in SBP) [1][2]

- Amylase level ↑ — suggests pancreatitis or gut perforation (every segment of gut except gallbladder leaks amylase into fluid when it perforates [2])

- Bilirubin level ↑ — suggests perforation of gallbladder into peritoneum (measured if fluid is dark orange or brown [2])

Summary Comparison Table: SBP vs. Secondary Peritonitis Ascitic Fluid

| Parameter | SBP | Secondary Peritonitis |

|---|---|---|

| Organisms | Monomicrobial | Polymicrobial |

| PMN count | ≥ 250/mm³ | Often much higher |

| Protein | ↓ (Low) — reflects poor opsonic activity [2] | ↑ (High) — protein-rich GI contents leak in |

| Glucose | ↑ (Relatively preserved) — fewer neutrophils consuming it [2] | ↓ (Low < 50 mg/dL) — massive neutrophil/bacterial consumption |

| LDH | ↑ (Mildly elevated) [2] | ↑↑↑ (Markedly elevated) — tissue destruction [2] |

| Amylase | Normal | ↑↑↑ if gut perforation or pancreatitis [1][2] |

| Bilirubin | Normal | ↑ if GB perforation [2] |

Exam Pearl: The Logic Behind SBP vs. Secondary

Think of it this way: SBP = bacteria are "tourists" that translocated into a fluid with poor defences. There aren't many of them, they don't destroy tissue, and the fluid hasn't been contaminated by GI contents → monomicrobial, low protein, preserved glucose, mildly raised LDH. Secondary peritonitis = a pipe has burst — GI contents (protein, bacteria, amylase, bile) flood the peritoneal cavity, massive neutrophil recruitment consumes glucose, tissue dies releasing LDH → polymicrobial, high protein, low glucose, very high LDH.

Investigation Modalities

Investigations for peritonitis serve three purposes: (1) confirm peritonitis, (2) identify the cause, and (3) assess severity/guide resuscitation. I'll organise these by modality.

A. Bedside Tests

| Investigation | Key Findings | Rationale / Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Urinalysis | Sterile pyuria (in diverticulitis/appendicitis adjacent to ureter), haematuria (ureteric colic), nitrites/leucocytes (UTI) | Sterile pyuria can occur from peritoneal inflammation irritating the adjacent ureter — don't be fooled into diagnosing UTI [1]. |

| Pregnancy test (urine β-hCG) | Positive → ruptured ectopic pregnancy | Must be done in ANY woman of reproductive age with acute abdominal pain [1][3]. A positive test completely changes your differential and management. |

| ECG | ST changes, arrhythmias | Rule out acute MI [3] — especially inferior MI which can mimic upper abdominal peritonitis via diaphragmatic irritation. Also check for AF (risk factor for mesenteric ischaemia). |

B. Blood Tests

Blood tests: CBC, LRFT, amylase, ABG, clotting, T&S [3]

| Investigation | Key Findings | Rationale / Why Order It |

|---|---|---|

| CBC with differentials | Leukocytosis (raised WCC with neutrophilia) [2] | The systemic inflammatory response to peritoneal infection drives bone marrow neutrophil release. In the elderly, leucocytosis may be the only clue to peritonitis when peritoneal signs are mild [1]. A left shift (bandaemia — immature neutrophils) suggests severe/acute infection. Leucopaenia is ominous (marrow exhaustion in overwhelming sepsis). |

| LFT | Deranged bilirubin, ALT, AST, ALP, GGT | Sepsis can lead to deranged liver function [2] — "septic liver" (cholestatic pattern from intrahepatic bile duct dysfunction due to endotoxins). Also baseline assessment in cirrhotic patients. Raised bilirubin + ALP may point to cholangitis as the cause. |

| RFT (renal function) | Raised urea and creatinine | Hypovolaemia leads to acute kidney injury [2] — pre-renal AKI from third-space losses. Also baseline for patients on nephrotoxic antibiotics (aminoglycosides). Raised urea out of proportion to creatinine suggests upper GI bleeding (urea from digested blood). |

| Serum amylase / lipase | Elevated ( > 3× ULN in pancreatitis) [2] | Pancreatitis as the cause of peritonitis. Also mildly raised in bowel ischaemia, perforated ulcer, and small bowel obstruction. Lipase is more specific than amylase for pancreatic pathology. |

| Serum protein / albumin | Hypoalbuminaemia | Massive protein loss into the peritoneal cavity (third-spacing). Also baseline for SAAG calculation in ascitic patients. |

| ABG with lactate | Metabolic acidosis, raised lactate | Raised lactate indicates tissue hypoperfusion (shock) or bowel ischaemia — a lactate > 2 mmol/L in the context of abdominal pain is a red flag for mesenteric ischaemia. Metabolic acidosis also seen in DKA (the medical mimic) [3]. |

| Clotting profile (PT, APTT) | Prolonged PT/APTT | Obtain baseline before endoscopic and surgical procedures [2]. Cirrhotic patients have impaired synthetic function → coagulopathy. DIC can develop in severe sepsis. |

| Type and screen | Blood group and antibody screen | Obtain baseline before endoscopic and surgical procedures [2]. In case emergency surgery is needed, blood must be available for transfusion. |

| CRP | Elevated | Non-specific inflammatory marker. Useful for monitoring treatment response. A CRP that fails to fall after treatment suggests uncontrolled source (abscess, ongoing leak). |

| Blood glucose | Hyperglycaemia (DKA, stress response) or hypoglycaemia (sepsis, liver failure) | Excludes DKA as a mimic. In CAPD peritonitis, infection will induce hyperglycaemia [2]. |

| Blood cultures | Organism identification | Must be taken before starting antibiotics. Aerobic + anaerobic bottles. Positive in ~30–50% of SBP. |

C. Peritoneal Fluid Analysis

This is the cornerstone investigation for primary peritonitis (SBP and CAPD). For secondary peritonitis, peritoneal fluid is often obtained intra-operatively rather than pre-operatively.

Ascitic fluid analysis by paracentesis [2]

Peritoneal fluid analysis [1]:

| Component | What to Look For | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Character | Serous, blood-stained, purulent, bile-stained, faeculent [1] | Serous = SBP or early infection. Purulent = established bacterial peritonitis. Bile-stained = perforated GB or biliary injury. Faeculent = perforated bowel. Blood-stained = trauma, malignancy, haemorrhagic pancreatitis. ↑ Amylase / bile-stained / faeculent indicates perforated GI tract [3]. |

| Cell count and differentials | Neutrophil count > 500/μL [1]; PMN ≥ 250/mm³ for SBP [2]; WBC ≥ 100/mm³ with PMN > 50% for CAPD [2] | PMN ≥ 250 cells/mm³ should be started on empirical therapy while awaiting culture results [2]. Lymphocyte predominance → TB peritonitis or malignancy. |

| Gram stain | Bacterial morphology | Quick but low sensitivity (~25% in SBP because bacterial density is low). Useful if positive (e.g., Gram-positive cocci in chains → Streptococcus). |

| Cultures | Aerobic, anaerobic, AFB, fungal [1] | Definitive identification. Inoculate into blood culture bottles at bedside. Monomicrobial = SBP; polymicrobial = secondary peritonitis. AFB culture takes 4–6 weeks and could be falsely negative [1]. |

| Albumin level | Calculate SAAG | Serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) = serum albumin − ascitic albumin (difference but NOT ratio [2]). SAAG > 1.1 g/dL = portal hypertension → SBP likely. SAAG < 1.1 g/dL = NO portal hypertension → think TB, malignancy, nephrotic syndrome [2]. |

| Protein level | High vs. low | ↑ Protein in secondary bacterial peritonitis; ↓ Protein in SBP [2]. Low protein in SBP reflects low opsonin activity (molecules that facilitate phagocytosis by macrophages) and patients are more prone to SBP [2]. |

| Glucose | High vs. low | ↑ Glucose in SBP; ↓ Glucose ( < 50 mg/dL) in secondary peritonitis [2]. Why? Neutrophils consume large amounts of glucose — secondary peritonitis has far more neutrophils → more consumption [2]. |

| LDH | Mildly vs. markedly elevated | ↑ LDH in SBP; ↑↑↑ LDH in secondary peritonitis [2]. Reflects degree of tissue destruction. |

| Amylase | Elevated | ↑ Amylase suggests pancreatitis or gut perforation — every segment of gut except gallbladder leaks amylase into fluid when it perforates [2]. |

| Bilirubin | Elevated | ↑ Bilirubin suggests perforation of gallbladder into peritoneum — measured if the ascitic fluid is dark orange or brown [2]. |

| Creatinine | Higher than serum | Ascitic creatinine > serum creatinine → bladder perforation / urinary leak [1]. |

| ADA (Adenosine deaminase) | Elevated ( > 39 U/L) | ↑ ADA level in tuberculosis infection [2]. ADA is a purine-degrading enzyme necessary for maturation and differentiation of lymphoid cells [2] — elevated because TB triggers a vigorous lymphocytic response. |

| Cytology | Malignant cells | Positive in < 10% of malignant ascites (poor sensitivity, in contrast with pleural fluid cytology with 70% chance of detection in malignant pleural effusion) [2]. |

D. Imaging

Imaging: ECG, Erect CXR, erect/supine AXR, USG, CT A+P [3]

| Modality | Key Findings | Rationale / When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Erect CXR | Free gas (pneumoperitoneum) under the diaphragm | The single most important initial imaging investigation in suspected perforated viscus. Free gas = hollow viscus perforation (PPU, perforated bowel). Look for free gas under diaphragm [2]. Also detects basal pneumonia (mimic), pleural effusion (reactive). As little as 1 mL of free gas can be detected on erect CXR. Must be erect for ≥ 10 minutes before shooting to allow gas to rise. |

| Erect and supine AXR | Dilated bowels in intestinal obstruction [2]; air-fluid levels; radio-opaque calculi; loss of psoas shadow (retroperitoneal pathology) | Supine AXR shows bowel gas pattern and distribution. Erect AXR shows air-fluid levels. Dilated small bowel ( > 3 cm) or large bowel ( > 6 cm, caecum > 9 cm) suggests obstruction. Free gas may also be seen on supine AXR as Rigler's sign (gas on both sides of bowel wall). |

| USG abdomen | Free fluid (Morison's pouch), gallstones, thickened GB wall, appendiceal diameter > 6 mm, adnexal pathology, abscess | Evaluation of acute cholecystitis, appendicitis and gynaecological infections [2]. First-line for RUQ pain (biliary) and suprapubic pain (gynae/urological) [3]. FAST scan in trauma to detect haemoperitoneum. Can detect as little as 200 mL of free fluid in Morison's pouch. |

| CT abdomen + pelvis (with IV contrast) | Free gas, free fluid, bowel wall thickening, fat stranding, abscess collections, mesenteric vessel occlusion, appendiceal inflammation | Gold standard for secondary peritonitis — identifies the source. CT is particularly useful for diverticulitis (CT scan helps to confirm diagnosis and assess severity [1]), appendicitis, and detecting intra-abdominal abscesses. Can guide percutaneous drainage. CT angiography for mesenteric ischaemia. CT with IV contrast is first-line for RLQ and LLQ pain [3]. |

| Colonoscopy | Mucosal pathology, stricture, tumour, colitis | Look for bowel ischaemia [2]. Used after resolution of acute inflammation to exclude CRC or IBD. AVOID endoscopy for acute abdomen — sealed-off perforation may open by gas insufflation during endoscopy [3]. |

| Diagnostic laparoscopy | Direct visualisation of peritoneal cavity | Used when diagnosis remains uncertain despite imaging. Diagnosis of TB peritonitis is often made by laparoscopy and biopsy of peritoneum [1]. Also therapeutic — can perform lavage, take biopsies, and even definitive surgery (appendicectomy, PPU repair). |

When NOT to Image — Go Straight to Theatre

Proceed to exploratory laparotomy if free gas / florid peritoneal signs [3]. If a patient has generalised peritonitis with haemodynamic instability, spending hours on CT delays definitive treatment. The surgical dictum: "If the clinical picture says operate, operate. CT is for when you're not sure."

Diagnostic Algorithm

The clinical approach follows a logical sequence: resuscitate → clinical assessment → bedside tests → blood tests → imaging → peritoneal fluid analysis → decide: operate or treat medically.

Step-by-Step Walkthrough

Step 1 — Resuscitate and Assess Simultaneously

You never wait for investigation results before starting resuscitation. A patient with peritonitis is losing fluid into the peritoneal cavity (third-spacing) and may be septic. IV fluid replacement, nasogastric tube, urinary catheter, oxygen [1] should be started immediately while you take the history, examine, and order tests.

Step 2 — Bedside Tests

- Urinalysis — excludes UTI, detects haematuria (ureteric colic), sterile pyuria (peri-ureteric inflammation) [1]

- Pregnancy test — mandatory in reproductive-age women [1]

- ECG — excludes inferior MI [3]

- Blood glucose — excludes DKA

Step 3 — Blood Tests

Blood count, renal and liver function, amylase, clotting profile, arterial blood gas, type and screen [1][3]. Blood cultures before antibiotics. The ABG with lactate is critical — a raised lactate > 2 mmol/L suggests tissue hypoperfusion or bowel ischaemia.

Step 4 — Initial Imaging (Erect CXR + AXR)

Erect CXR is the first imaging — looking for free gas. If present, you have a perforated viscus and may proceed directly to surgery. Erect and supine AXR — look for dilated bowels (obstruction), air-fluid levels, calculi.

Step 5 — Decision Point: Free Gas?

If free gas + florid peritoneal signs → proceed to exploratory laparotomy [3]. Do NOT delay with further imaging in an unstable patient.

If no free gas but peritoneal signs present → further investigation needed to identify the source.

Step 6 — Further Imaging / Fluid Analysis

- Cirrhotic with ascites: Diagnostic paracentesis → ascitic fluid analysis (cell count, culture, protein, glucose, LDH, albumin for SAAG, ± amylase/bilirubin/ADA/cytology) [2]

- PD patient: Collect PD effluent for cell count + culture [2]

- All others: USG abdomen for RUQ/pelvic pathology; CT abdomen + pelvis with contrast for most other scenarios [1][2][3]

- If diagnosis remains elusive: diagnostic laparoscopy [1]

Step 7 — Classify and Treat

Based on the above, classify as primary (SBP/CAPD/TB) vs. secondary (surgical source) vs. tertiary (persistent/opportunistic) and institute appropriate management.

Investigation Selection by Site of Pain

This is a practical guide from the clinical approach [3]:

| Site of Pain | Imaging of Choice |

|---|---|

| RUQ | USG (biliary pathology — cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis) |

| LUQ | CT (splenic pathology, pancreatitis) |

| RLQ | CT with IV contrast (appendicitis, right-sided diverticulitis, Crohn's) |

| LLQ | CT with IV contrast (left-sided diverticulitis, sigmoid pathology) |

| Suprapubic | USG (TAS or TVS) (gynaecological, bladder pathology) |

| Diffuse | Erect CXR first, then CT abdomen + pelvis if no free gas [3] |

Special Investigation Scenarios

TB Peritonitis

Peritoneal fluid: AFB smear often negative, culture would take 4–6 weeks (could be falsely negative) [1]. This makes diagnosis challenging. Key investigations:

- Ascitic fluid: Lymphocyte-predominant, high protein ( > 2.5 g/dL), ↑ ADA level [2], low SAAG ( < 1.1 g/dL)

- Diagnosis often made by laparoscopy and biopsy of peritoneum [1] — looking for caseating granulomata and "millet seed" tubercles studding the peritoneal surface

- Interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) / Mantoux can support but not confirm peritoneal TB

- PCR for M. tuberculosis DNA in ascitic fluid — increasing role

Diverticulitis-Related Peritonitis

CT scan helps to confirm diagnosis and assess the severity [1]. CT findings include:

- Colonic diverticula, localised bowel wall thickening ( > 4 mm), pericolonic fat stranding

- Abscess (fluid collection with air/debris), free gas (perforation), fistula tracks

- Hinchey classification applied based on CT findings to guide management [6]

High Yield Summary — Diagnostics

Diagnostic Criteria:

- SBP: PMN ≥ 250/mm³ + positive culture + secondary causes excluded. SAAG > 1.1 = portal hypertension → SBP likely. Monomicrobial.

- CAPD peritonitis: Clinical features (pain/cloudy effluent) + WBC ≥ 100/mm³ with PMN > 50% (dwell ≥ 2h) + positive culture. Lower threshold than SBP due to dextrose-enhanced bacterial growth.

- Secondary peritonitis (Runyon's): ≥ 2 of: protein > 1 g/dL, glucose < 50 mg/dL, LDH > ULN. Polymicrobial. Needs surgery.

Key Investigations:

- Bedside: Urinalysis, pregnancy test, ECG, glucose

- Bloods: CBC, LRFT, amylase, ABG/lactate, clotting, T&S, blood cultures

- Imaging: Erect CXR (free gas!) + AXR → USG or CT A+P

- Peritoneal fluid: Character, cell count, Gram stain, cultures (aerobic/anaerobic/AFB/fungal), albumin (SAAG), protein, glucose, LDH, amylase, bilirubin, creatinine, ADA, cytology

Decision Rule: Free gas on erect CXR + florid peritoneal signs → exploratory laparotomy (do NOT delay with further imaging).

SBP vs. Secondary: SBP = monomicrobial, low protein, preserved glucose, mildly raised LDH. Secondary = polymicrobial, high protein, low glucose, very high LDH.

Active Recall - Diagnosis and Investigations of Peritonitis

1. State the diagnostic criteria for SBP and explain why the PMN threshold is 250/mm3 rather than 500/mm3.

Show mark scheme

SBP requires ALL of: (1) Ascitic fluid PMN >= 250 cells/mm3, (2) Positive peritoneal fluid culture, (3) Secondary causes excluded. The threshold is lower at 250 (not 500) because cirrhotic patients are immunosuppressed and mount a weaker inflammatory response; waiting for 500 would miss early SBP and delay life-saving antibiotics. The 250 cut-off has ~93% sensitivity.

2. Why is the WBC threshold for CAPD peritonitis (100/mm3) lower than for SBP (250/mm3)?

Show mark scheme

PD fluid contains dextrose which provides an excellent growth medium for bacteria, leading to rapid bacterial proliferation. Even a lower WBC count indicates significant infection in this environment. Without antibiotic therapy, bacteria multiply quickly in the dextrose-rich PD fluid, so a lower threshold ensures early detection.

3. A cirrhotic patient with ascites develops peritonitis. Ascitic fluid shows: protein 1.5 g/dL, glucose 30 mg/dL, LDH above ULN, polymicrobial culture. Is this SBP or secondary peritonitis? Justify using Runyon's criteria.

Show mark scheme

This is secondary peritonitis. Runyon's criteria met (all 3 of 3, need >= 2): protein > 1 g/dL (1.5), glucose < 50 mg/dL (30), LDH > ULN. Additionally polymicrobial culture confirms secondary peritonitis. This patient needs CT to identify source and likely surgical intervention, not just antibiotics.

4. What does a SAAG > 1.1 g/dL indicate and how is it calculated? What does SAAG < 1.1 indicate?

Show mark scheme

SAAG = Serum albumin minus ascitic fluid albumin (difference, NOT ratio). SAAG > 1.1 g/dL indicates portal hypertension (cirrhosis, heart failure, Budd-Chiari) and thus SBP is a likely cause of peritonitis. SAAG < 1.1 indicates no portal hypertension - think TB peritonitis, malignancy, nephrotic syndrome, pancreatic ascites.

5. When should you proceed directly to exploratory laparotomy without further imaging in suspected peritonitis?

Show mark scheme

When there is free gas under the diaphragm on erect CXR AND/OR florid peritoneal signs (diffuse tenderness, guarding, rigidity, rebound) with haemodynamic instability. Do not delay with CT or other imaging in an unstable patient with clear signs of perforated viscus and generalised peritonitis.

6. List 3 ascitic fluid findings that specifically point to a perforated GI tract rather than SBP.

Show mark scheme

(1) Raised amylase - every segment of gut except gallbladder leaks amylase when perforated; also pancreatitis. (2) Bile-stained fluid - suggests gallbladder/biliary perforation. (3) Faeculent fluid - perforated bowel (colonic). Also: raised bilirubin (dark orange/brown fluid = GB perforation), polymicrobial culture, Runyon's criteria positive (high protein, low glucose, high LDH).

References